What is it? A sci-adventure where you navigate an alien ocean through a computer interface

Price $15 / £12

Release date April 3, 2020

Publisher Fellow Traveller

Reviewed on i5-2500K, 8GB RAM, GTX 670

Developer Jump Over The Age

Multiplayer No

Link Official site

The way that In Other Waters imagines humanity’s first encounter with alien lifeforms is a bit different from other sci-fi stories. Instead of alien species raging war against Earth or the vast spectacle of humans conquering other inhabited planets, developer Gareth Damian Martin’s otherwordly adventure takes a more gentle approach. It’s a quiet and serene adventure in which you explore an underwater eco-system told through the descriptions of a scientist.

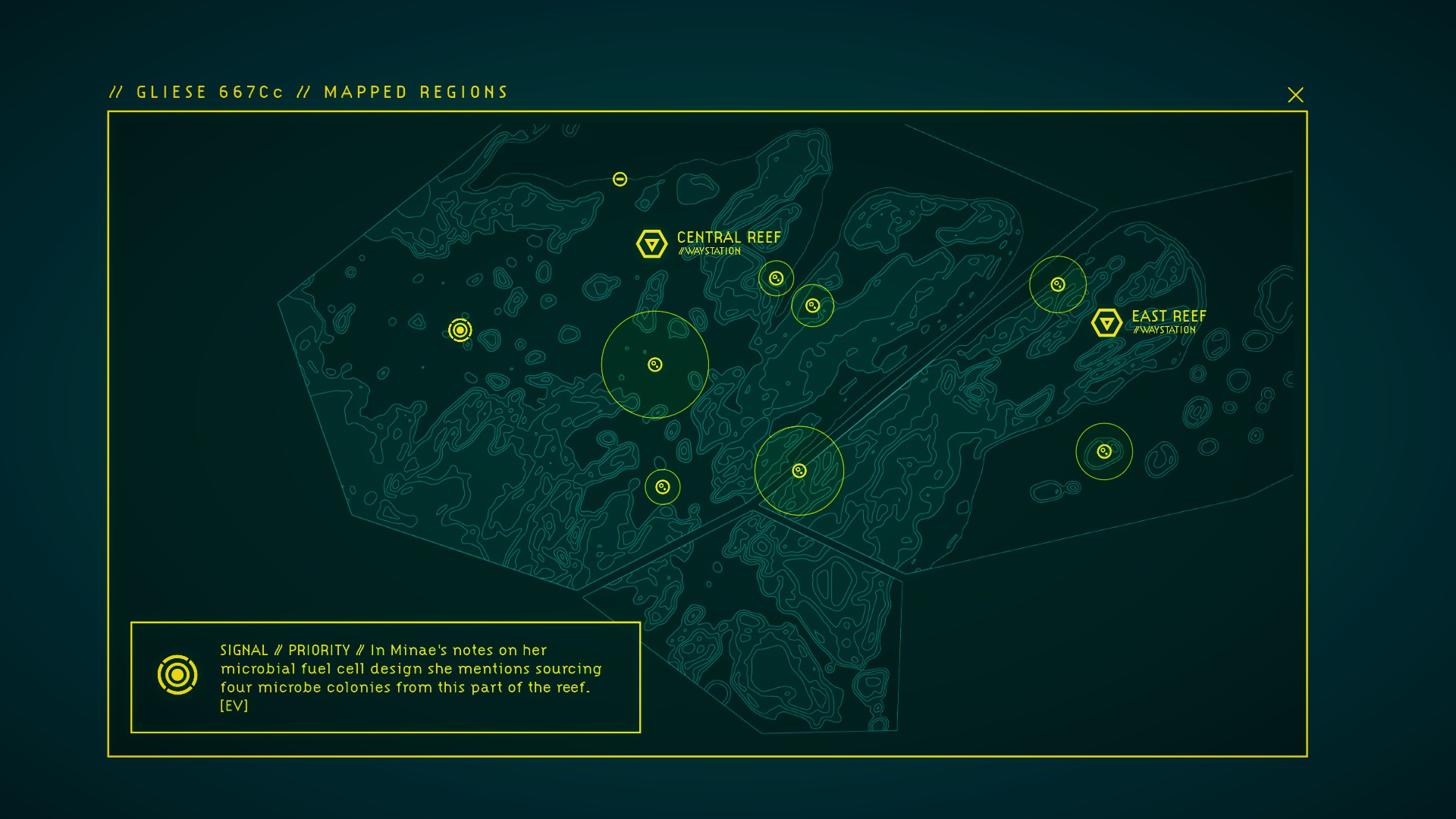

Beneath the turquoise waves of the planet Gliese 677Cc is a thriving alien eco-system. It’s an ocean filled with mystery and discovery, and In Other Waters is a fine-tuned balance of awe and trepidation, creating an underwater adventure like no other.

You play as the computer AI of an exo-suit piloted by xenobiologist Ellery Vas, a scientist who has come to Gliese 677Cc to study the planet’s strange lifeforms and find her fellow scientist, Minae Nomura, who has not been seen in months since arriving on the planet. The story follows Ellery as she traces her lost colleague’s footsteps through the depths of this alien ocean, trying to understand what Minae was studying in secret.

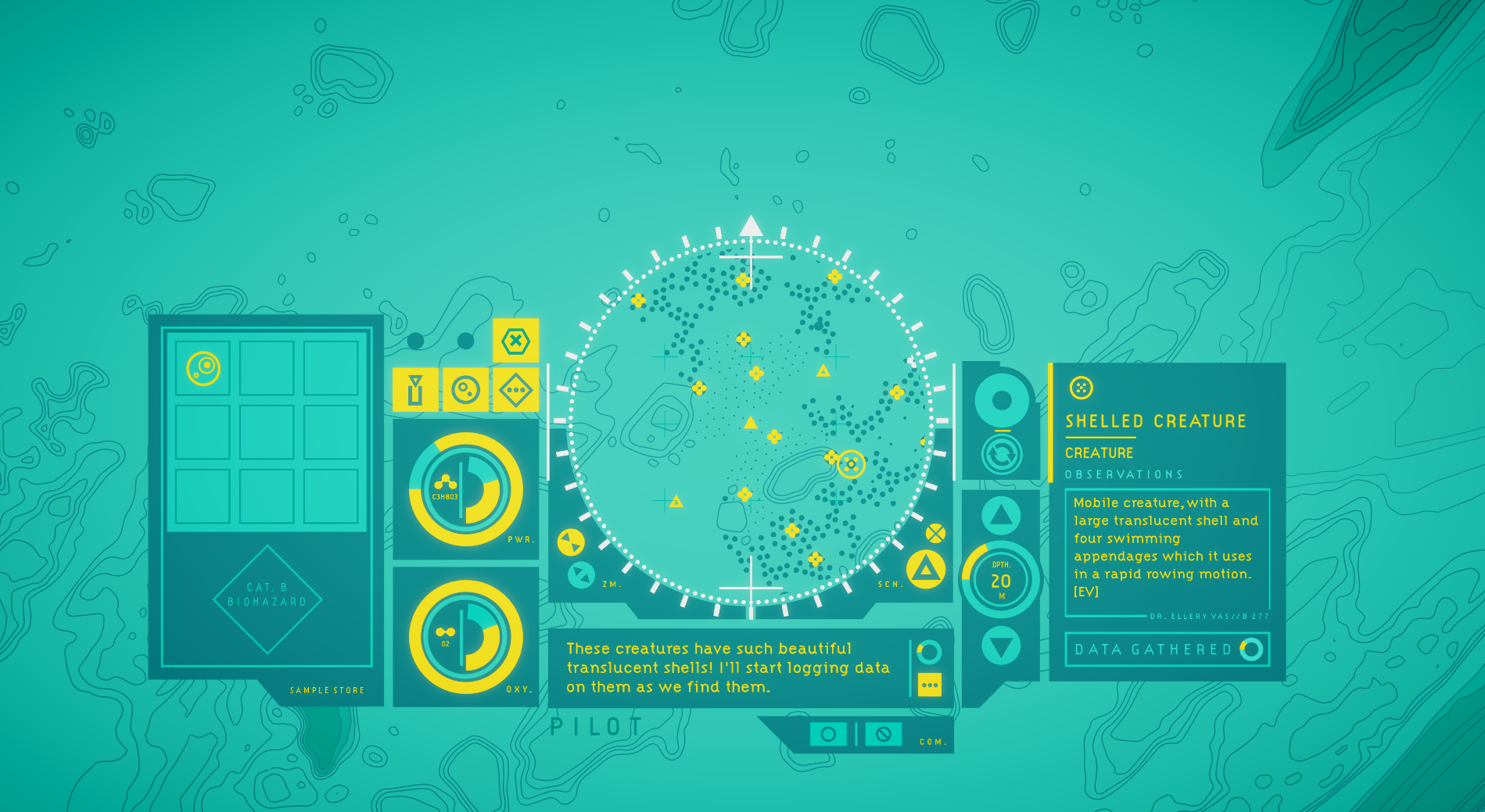

You assist Ellery as she navigates the underwater landscape of this new world through a computer interface. The circle in the middle of the UI displays a sleek, minimalistic map of your surroundings covered in lines, dots and symbols. You scan your surroundings and then decide where Ellery is going to move, with her taking notes and making observations about the ecology and geography as you go.

Ellery’s vivid descriptions of your surroundings are your only way of making sense of the world, bringing those lines and symbols to life. As we make our way through the landscape, a dot on the map speeds towards us and I immediately think it’s going to attack us, but Ellery calms my fears and explains that it’s only a friendly jelly-fish like a creature. Where I only see jagged lines of rock outlines on the interface’s sleek design, Ellery says that we are standing on the edge of a vast underwater reef teeming with life. Until her description, the symbols and lines around us are a mystery. As long as Ellery is calm, I am calm, when she panics, I panic. It’s a vulnerable feeling, having to rely on her to be my eyes, even though she’s the flesh and blood my circuits are meant to protect. The dynamic gave me a sense of responsibility to her and her endeavor, fueling my motivation to explore deeper.

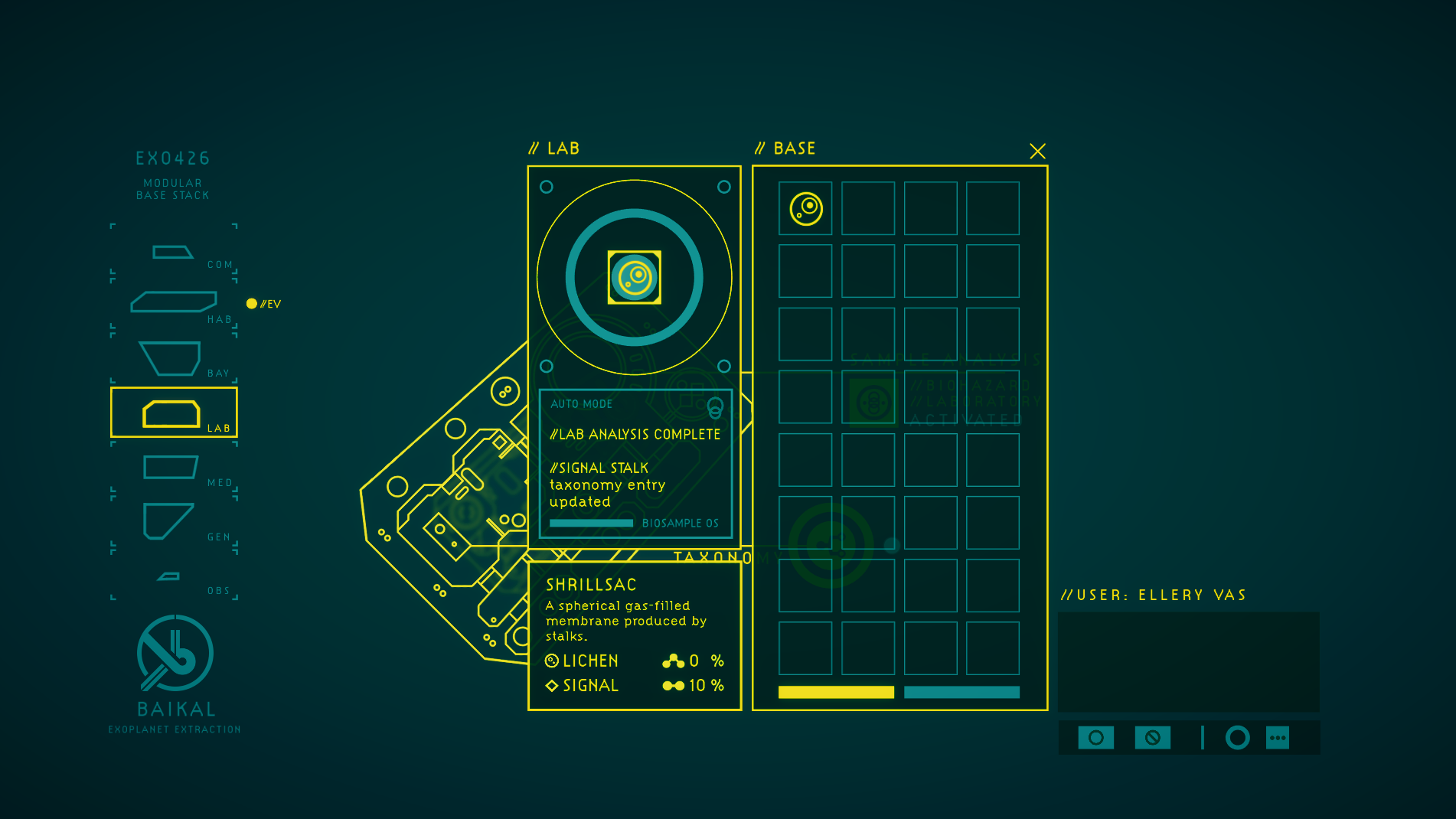

In the same vein as old text adventure games, these descriptions build a strong mental picture of this world’s alien ecosystem. Along with her visual descriptions, Ellery logs the species’ behaviours and gives observations and educated guesses about how they fit into the larger ecosystem. The writing is vivid to the point where it feels like I’m learning about a real ecosystem. The ‘singing’ of underwater stalks could be communication system, Ellery says, and their growth pattern implies a complex territorial network—you get the sense that a lot of research has gone into making this otherwordly ecosystem as believable as possible.

The sound design reinforces the word-built world: Creatures chirp when they speed past you, acid clouds fizzle as they gnaw at the underwater suit. As you go deeper into a cavern the soundscape adjusts to a deeper timbre, pulling you into the depths. Together with the bleeps and bloops of the interface and Amos Roddy’s warm synth soundtrack, it creates a rich alien soundscape.

Ellery isn’t here on holiday, though, and research is always at the forefront of her mind. Part of the interface allows you to take small samples from the flora and fauna you come across. At the research base, you can analyse them in the laboratory and the data is added to your alien encyclopedia, a log that holds all the information about each species you’ve encountered. You have the option of going back to previous areas to collect samples that you might have missed with a map indicating their locations. It’s not essential, but completionists can enjoy the relaxing collect-a-thon if they like.

Your inventory of organic samples can also be cleverly used as resources on your expeditions. Some can give you an oxygen boost when Ellery’s running low and others can even influence the world, such as by making a bunch of alien stalks retract to clear the way through a cavern. It takes careful thinking to progress with what resources you have, so navigation is more than a rote cycle of scanning and moving.

There were a handful of occasions where I got lost exploring In Other Waters’ ocean of words. If you forget or misunderstand what the next task is, it can be difficult to proceed. There are conversation logs to re-read, but with all the terminology and species names to remember, I ended up resorting to trial and error on occasion.

Otherwise, though, In Other Waters pulled me through fields of alien fauna, caverns filled with glowing acid pools, through powerful currents that could sweep me away, and to the dark depths of the ocean’s lower floors. In moments, it captures both the beauty and terror of the ocean. That coupled with the detailed ecosystem and the mystery of Minae’s secret work had me spellbound until the end.

Even though its world is alien, In Other Waters conjures the same sense of awe conjured by the real ecosystems of our own planet. Even in the most inhospitable places, life manages to find a way to thrive.

Read our review policy

A gentle and engrossing underwater sci-fi game that will have you thinking about more than what lies beneath the waves.