What is it? An open-world game dedicated to smooth, fast movement and boss fights.

Expect to pay: $40/£32

Developer: Giant Squid

Publisher: Annapurna Interactive

Reviewed on: GeForce GTX 1650, AMD Ryzen 5 3550H, 8 GB RAM

Multiplayer: No

Link: Official site

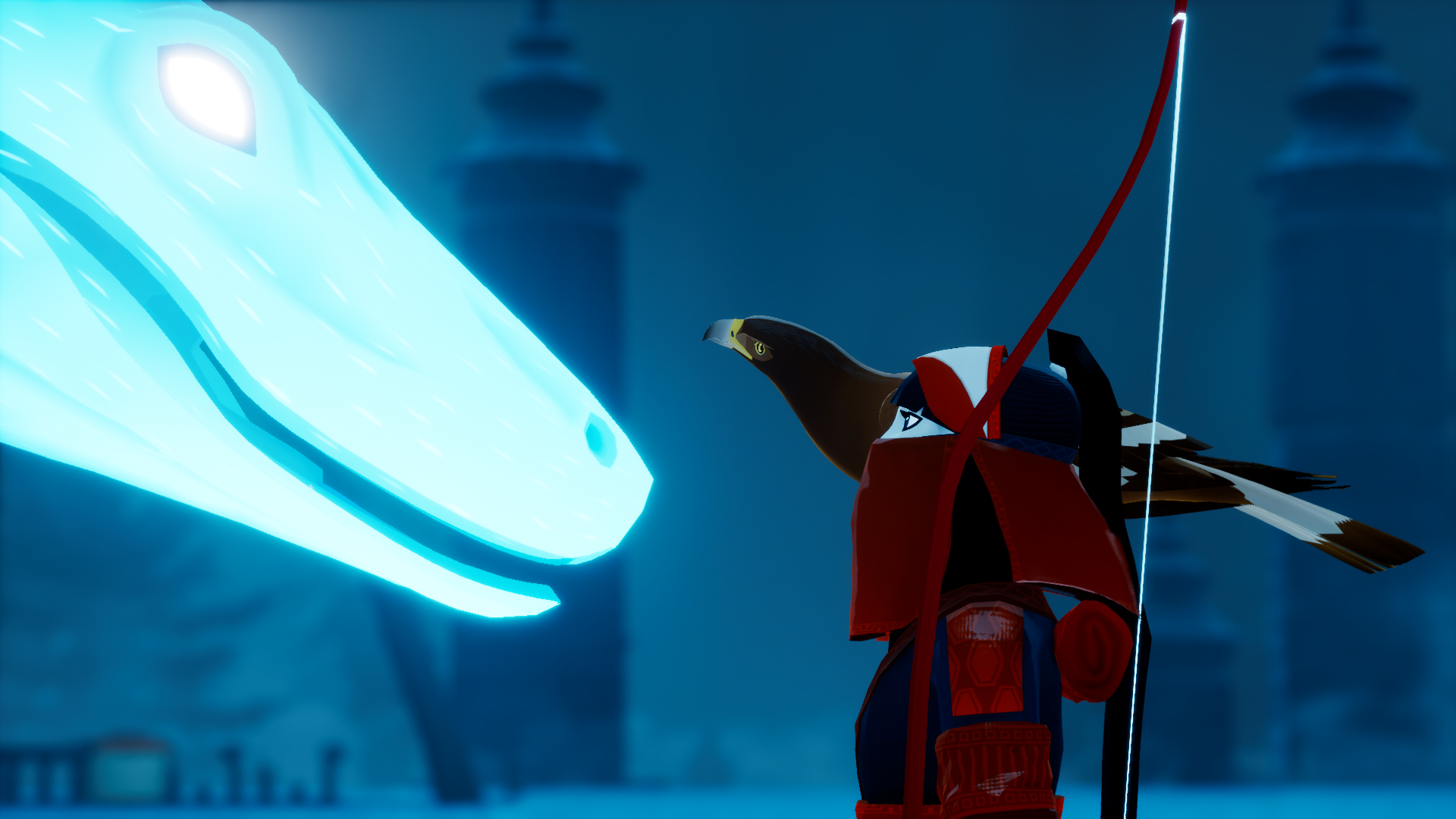

The Pathless is notable in part for all the things it doesn’t have. It’s an open world game with no minimap, no fast travel, no player deaths, no enemies apart from bosses, no NPCs, and no vehicles whatsoever—just an eagle companion and a bow and arrow. Yet what it does have has been so expertly crafted that the end result is remarkable.

The foundations of the story are familiar—a fantastical land has been overrun by an evil curse, and it’s up to you to be a heroic mop and clear up the mess—but don’t be fooled. The Pathless isn’t quite like anything else, something that becomes apparent within seconds of taking your first dash across a field: Your sprint is powered by a meter that depletes rapidly, but that can constantly be topped up by shooting floating talismans.

You don’t have to manually aim at the talismans, at least not in the traditional sense. When you get close enough to a target and/or point the camera towards it, it’s automatically highlighted, and all you need to do is to hold down a button for a second and then release. Travelling on foot at speed is almost like an extended (but actually enjoyable) QTE, whereby you rush to your destination while carefully timing your shots to keep that meter alive. Simply moving from one place to another is a light challenge and a joy.

Your hunter does have one special power in the form of ‘spirit vision’. This is first introduced as a way to pass through clearly-marked walls, but the sheer genius of this idea comes to light once you start trying to work out what to do and where to go. There is no map of any kind, and no waypoints. Engage spirit vision, and everything turns a lovely shade of blue, with areas of interest pulsing red. There’s often no indication of precisely what is there—whether it’s one of the items necessary to progress the story, or an area hiding an optional collectible—but you can guarantee that it’ll be something worth finding.

Although the idea of a Detective Mode a la Arkham is now widely understood, it’s ordinarily used to show the player exactly what they need to see, and often down a linear path. Here, the player rather than the developer chooses when and how it is used, and the telltale pulse of an area of interest disappears when you get close. It’s a wonderful balance between player freedom and developer assistance.

Eagle aid

The world offers puzzles in place of enemies, and I enjoyed all of them. They test your brain without being obnoxious; I never got stuck for more than a minute or so, and even that was rare. This isn’t an indication of puzzles that are too easy, rather another sign of the game’s dedication to constant, smooth motion.

Your eagle and your bow tend to be of equal importance in these puzzles. You’ll need to shoot arrows through consecutive targets, for example, but lining them all up will often involve asking Keith, your eagle (that’s not its name, but let’s pretend) to help. Keith will need to move targets, perhaps, or lift weights to bring to pressure plates. He’s only able to carry one thing at a time, so he can’t lift you into the air while he’s already got something in his talons. This caused me a bit of a head scratch when I found a weight on the ground, and a pressure plate about a hundred feet in the air.

Outside of puzzles, I enjoy finding the thoughts of dead soldiers frozen in time, and admiring the abandoned temples, curious structures, and skeletons of huge, unknown beasts that have been left lying around. Sometimes, I’ll get the best views soaring through the air, hanging from the feet of my remarkably strong eagle as we gently drift down to our next destination.

Find your way

I have two criticisms. Firstly, before you’re ready to face them, an area’s boss will sometimes trigger an event whereby you’re separated from your eagle. You then need to slowly creep over to rescue it, periodically stopping whenever the big bad’s gaze falls your way. This becomes tiresome after just a few times. Secondly, once you’ve got your bird back, you need to cleanse it by simulating a stroking motion all over until all of the curse juice is gone. I know this is meant to build a bond, but it also becomes annoying after a while. Also, one of the boss fights went on a bit too long when I struggled to hit multiple weak spots in a row. OK, fine, three criticisms.

I just can’t stay angry at this game. The main motivation for the villain’s evil deeds is a desire to provide everybody with a strict path to follow in life, which seems to be something of a commentary on Giant Squid’s approach to designing the entire game. While bosses follow a fairly rigid pattern—a chase to hit weak spots, an arena fight to hit weak spots, then one or two final stages to hit weak spots—the bulk of the game does not. You ‘unlock’ boss fights by collecting and using certain items, but each area of the map has more than you actually need. The items you collect, and the order in which you collect them, are dependent on nothing more than where your curiosity takes you; and in the unlikely event that a puzzle stumps you, there will be another a few minutes’ journey or less away.

The story comes to a satisfying end, after which I gleefully jumped back in to start mopping up the remainder of the puzzles. The cherry on top is the soundtrack, a typically wonderful Austin Wintory score that incorporates the superb sounds of throat singing band Alash. The Pathless sacrifices difficulty at the altar of fun, and it works superbly.

Read our review policy

A smooth and mesmerising experience that includes nothing it doesn’t need.