Medal of Honor: Above and Beyond takes an everything-but-the-kitchen-sink approach to VR game design, throwing you into European WW2 combat scene after European WW2 combat scene: parachuting behind enemy lines, manning an AA gun, clearing a Nazi train, riding shotgun in a motorcycle, storming Omaha beach. It all sounds more exciting than it actually is. I was bored often, especially during the dull mission briefings and bits of dramatic dialogue that bookended action segments. Held captive by my VR headset—I played with a first-gen Oculus Rift—I sometimes felt outright mad at Above and Beyond for not getting on with it.

You can come unstuck and have an out-of-body experience, turning around to see your own headless torso.

When it’s being merciful, Above and Beyond at least lets you goof off during its weirdly-paced dialogue scenes (lots of long pauses). I threw props around, and if it let me, plunked holes into my surroundings with my pistols and rifles and submachine guns. Admittedly, that means I’m judging with an incomplete experience of the dialogue, because a lot of it went like: “There are things [inaudible because I started firing my handgun into the ceiling] that I’m willing to sacrifice myself for.” I got the gist, though, and it’s all the usual boring suspects: clean-cut American good guys, a plucky British teenager, some French resistance fighters.

When it’s being cruel, Above and Beyond makes you restart a scene because you ‘blew your cover’ by messing around and shooting at the floor. In those moments, it feels like I’m being punished by the teacher for not paying attention during class. Sometimes it even glues you in place so that all you can do is stand and listen. (Amusingly, though, you can come unstuck and have an out-of-body experience, turning around to see your own headless torso.)

Above and Beyond isn’t always more enjoyable when the shooting starts. Sometimes I’d pop out of cover and almost instantly everything would go echoey and red to warn me I was taking too much fire—some of the Nazis are absolute lasers with their rifles. There wasn’t much time to awkwardly aim down the sights of my M1 Garands or Gewehr 43s, then, so I shot from the hip and relied on tracer bullets and generous hitboxes to clear out enemies as fast as I could, skating around with the analog stick on my left Oculus Touch controller. (There are other locomotion options.)

It’s fun in moments, but most of the challenge is remembering to stock up on ammo and reloading as speedily as possible—I was almost always thinking about ammo. The magazines don’t snap to their slots in the satisfying way they do in Half-Life: Alyx, though. For how much I had to think about reloading, it’s not very satisfying. Even the ping of a spent M1 Garand clip is hard to hear. (I used the built-in Oculus Rift headphones.)

I started having more fun when I turned the difficulty down to get past an awful Norway skiing segment (you ski very, very slowly while being shot at). On easy, there’s noticeable auto-aim that makes just about every other shot a headshot. I liked it that way, even though there was no skillfulness to it, because pretending to be a crack shot without really being one was more fun than squinting down my sights at deadly clumps of pixels up on balconies.

If you’re working with older VR hardware like me, know that there’s a good amount of shooting at range. There are sniper rifles to help, but they’re horrible to use—the scopes flatten the world, and I had to cross my eyes to bring them into focus. Additionally, if you don’t have 360-degree tracking, it’s very easy to accidentally get turned around in Above and Beyond.

All of the above

What was fun in Above and Beyond was holding my handgun sideways, and otherwise attempting to shoot Nazis in ways uncharacteristic of the early 20th century. I also liked jabbing my chest with syringes to heal, an ultra-violent action that I did casually, as if idly jabbing pins into a cushion. VR games, whether or not they intend to be, are great comedic vehicles. It was especially funny when I syringed myself on accident while trying to grab a gun—but also annoying, since a useful item was wasted. Likewise, grabbing a grenade when I meant to grab a syringe was only funny a few times. The funniest thing that happened was when I desperately reached for my submachine gun and ended up holding a potato in front of my face.

I did enjoy the scenery a good deal, especially some of the interiors, which are filthy with little details, like books and pamphlets and newspapers—I wouldn’t have accepted anything less, since the damn game devours 180GB of disk space. Outside, there are some stunning vistas, and an incredible number of distinct scenes and set pieces. Just the number of landscapes produced for this game is a hell of an accomplishment.

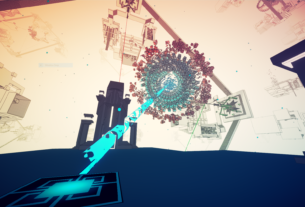

With so much variety, there’s some enjoyment to be had just from seeing how the devs approached each scenario. No scene is totally successful, and there are some real stinkers: infiltrating a Nazi base by walking around with a box of papers, a dreadful nautical stealth segment, an underwater bit where you have to wave your arms to swim (just awful), a scene where you shoot down planes that just kind of get stuck in the ocean when they crash (this whole scene is bizarrely janky). But some are stupid in a fun sort of way. When you climb into a tank, for instance, the cannon follows the center of your vision, and it feels as if you’ve become the tank. It isn’t more fun than any other on-rails tank combat level—look at Panzerschreck guys, shoot them with the machine gun—but after defeating a Tiger tank you’re off to do something totally different.

It’s like wandering between lavish but disappointing interactive museum exhibits. You know turning the valves in the U-boat isn’t going to be more fun than pretending to be a janitor in the Nazi facility (you have to bend down and pick up trash to blend in), but you still want to check it out.

Speaking of museums, the campaign itself is obviously not a documentary—it’s about soldiers having a good time and playing by their own rules—but there are also History Channel-style documentary videos about the war, which include interviews with veterans, as well as some real 360-degree photographs (of craters and ruins, for example). You have to unlock all that by playing the campaign, which seems silly. They’re history videos, not Destiny 2 exotics. It’s a nice inclusion, though, and made me feel nostalgic for ’90s multimedia CD-ROM encyclopedias. (Not really something you need to be in VR for, though.)

Above and Beyond also includes a survival mode and multiplayer. For some reason, you don’t have a sidearm in multiplayer, which means that fast reloading is even more vital than it is in the campaign—reload or you’ve got no gun at all. I found that annoying, but I had fun in multiplayer. Many of my opponents were bots, and the bots are prone to standing still. Fun for me to shoot. I easily camped the enemy spawn in a point capture mode, too, so I don’t get the sense that this is going to be a competitive gaming phenomenon. I’d still rather play Rainbow Six Siege or Valorant for that kind of experience.

Medal of Honor: Above and Beyond does go above and beyond in ways. It’s longer than I expected, bursting with one-off experiences and multiplayer modes and extras. And I can’t say it betrays the spirit of 2002’s Medal of Honor: Allied Assault, which was one of my favorite games when I was a teenager. The M1 Garand still goes ping, if quietly, and the beach assault scene is basically the same, with some added explosives to plant as you run between anti-tank obstacles. But it’s nearly 20 years later, and Steven Spielberg directs stuff like Ready Player One now. Even in the still young medium of VR, Medal of Honor: Above and Beyond feels outdated.