Pendragon is easily one of the oddest and most unique games I’ve played all year. Drawing from some rather varied inspirations — primarily chess and FTL — it’s ostensibly a roguelite turn-based tactical game themed around Arthurian legends. It’s actually a storytelling mechanism which uses turn-based strategy combat to influence and expand on that story.

If that doesn’t make sense, don’t worry. For one thing, it took me a little while to wrap my head around the hows and whys of it. For another, I’m hopefully going to actually explain it here.

Pendragon is set around the end of the Arthurian cycle. Camelot has fallen, the knights are scattered, and Britain is under the thumb of Mordred. The heroes are all old and broken and the Battle of Camlann, where King Arthur is fated to die, is nigh.

You pick one of those broken heroes, generally pulled from either Arthurian legend or related Celtic myths. And then you ride to Camlann to determine the fate of the nation.

The beginning of the end

The “victorious” end is pre-determined: you’ll reach Camlann, face Mordred, and win. But Pendragon kinda doesn’t care if you win or lose. It cares about the story that happens, and quite often, the most interesting stories come from ignominious failures.

The moment-to-moment gameplay is, as noted above, very similar to chess interspersed with FTL. You pick a destination, and a battle will likely happen there. Victory comes from defeating or scaring off all enemies, or by reaching a tile on the far side of the board.

Characters often have their own thoughts on good moves to make. While usually sensible, you still want to think them through.

Both you and the AI can move one character per turn, they can generally move one tile, and one hit is all that’s needed to kill another unit. There’s a lot more nuance to it than that — there’s a degree of territory control that lets you move multiple spaces, a diagonal stance that allows movement in other ways but disables attacks, and characters have special abilities that might let them attack or move in otherwise impossible ways. You can also afford to “lose” a unit. As long as you win the battle and it has health left, it’ll survive. But for the most part, you’re making one very careful move and then reacting to your opponent.

So yes, the overriding feeling when playing Pendragon was that of playing chess with a few pieces. I’d dance around looking for an opening to take a unit/piece without exposing my own to danger, or without sacrificing one. But that’s where things get interesting.

A worthy sacrifice

Like I said, Pendragon is mostly interested in creating a story, and anything that advances the story is rewarded in some way. This includes losing units. Depending on your choices, your Guinevere may be a loving queen forced into hiding and desperately trying to save Arthur. However she starts out, she’ll likely pick up friends and allies along the journey.

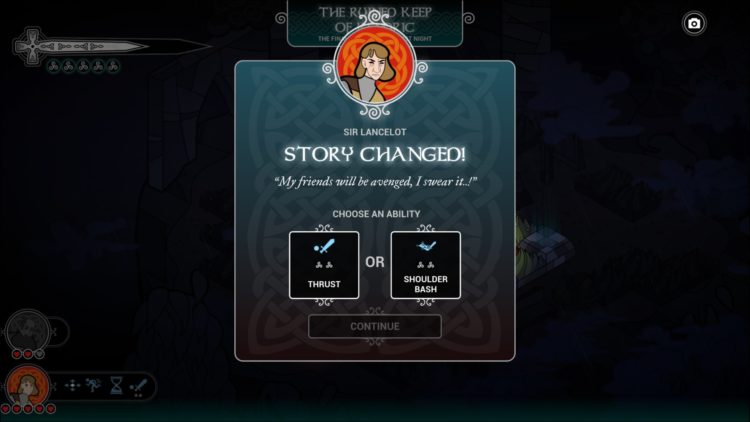

But if a companion is killed or a battle forces her into a blind rage, that personality may shift to being more vengeful and angry. Her skills will change accordingly: more defensive, movement based skills may become abilities that let her attack without moving, or even strike diagonally. Your units don’t get “better” by winning battles or kill units. They change based on the plot.

And while defeating Mordred is your ultimate aim, the game tends to treat most completed stories as being a success of some sort. Honestly, some of the most entertaining runs I’ve had were dramatic failures — with an emphasis on “dramatic.”

Pendragon: The Tragedy

One of my most recent tales started with Lady Rhiannon, a reckless sword-wielder raised in the wilds and an entertaining choice of protagonist. Her early journeys took her alone through forests and dells, until she met up with Lady Teleri, an aging knight. The two were ambushed by Mordred’s knights, and Rhiannon was cut down — but Teleri won the day and saved Rhiannon, earning her respect.

Soon after, they bumped into Queen Guinevere. A horrible wounding by knights caused Rhiannon to fly into a rage and butcher a half-dozen of them, and the three companions continued on to a beautiful glade. Where, uh, Rhiannon was killed by a badger. And Guinevere sounded a retreat.

So, my protagonist was dead, but the story continued. Teleri was savaged by wolves, but Guinevere wasn’t alone for long: she soon encountered the witch queen Morgana. Despite some mutual distrust, Morgana wanted to give her nephew Mordred a good hiding and couldn’t be dissuaded from coming along. Wolves caused more trouble, but Sir Gawaine swooped in like a deus ex machina to save the duo, and joined the party.

Badgers are terrible murder-beasts, everyone.

Alas, Guinevere’s wounds and the lack of rations were adding up, and Arthur’s queen fell ill. A local villager offered to assist — and under the pretense of administering medicine, he fatally poisoned her, hoping for a reward from Mordred. In a rage, Morgana then promptly murdered the entire village.

The next villagers they met were actually friendly (or had heard about Morgana’s penchant for angry carnage and didn’t want to risk antagonizing her) and one signed up, but this alliance was short-lived. A battle against another huge pack of wolves led to both Gawaine and the villager falling, and Morgana’s battle rage didn’t last long enough to win the day. When the red mist lifted, she was too exhausted to continue fighting, and the three were devoured by wild animals.

That was one game of Pendragon. There were multiple deaths of my would-be “protagonists.” Multiple failures and flights from combat. Basically none of it was scripted. And it was fascinating and exhilarating; it evolved and changed my characters as they failed; and it was honestly more interesting then going to Camlann and punching Mordred in his stupid beardy face.

Camelot’s fall

Almost every move you make, even in combat, leads to a line or two of text.

The tactical nuance and evolving storylines are stirred into a pot with decent writing and gorgeous still art. Better still, the entire atmosphere reeks of foreboding. This isn’t a shining legend of Arthur saving Britain. It’s a collapsing world where the heroes are wrestling with their own demons, once-mighty castles are crumbling ruins, everywhere feels overrun and wild, and the quest is seemingly hopeless. So, y’know, very cheery and upbeat.

But it’s also not perfect. Across the hours you tend to see a lot of events repeat, but the nature of the combat means you can’t just go on autopilot. Text simultaneously moves a bit too fast and not quite fast enough, even with the speed slider settings. There are also a fair few randomized side characters (like the aforementioned Lady Teleri or the random villager whose name I can’t remember) who have a place in your Pendragon story, but simply aren’t interesting.

Why do we fall, Bruce? To get our allies different abilities.

I think it’s also of limited appeal to those who are solely after a true tactical experience. While there are a lot of smart plays to be made here, and while one wrong move can back you into a corner, the losses and the way they change things are far more interesting than simple victories. Indeed, the campaigns where I’ve steamrolled my way to Camlann have been the most boring of games, primarily because they’ve been the most boring of stories.

Pendragon isn’t a game I’d recommend to everyone. However, as a way of telling emergent stories that aren’t quite emergent, it’s absolutely fascinating. Those with a fondness for the Arthurian cycle or old Celtic myths will enjoy immersing themselves in this world; those who love exploring the way games can tell stories will be fascinated by the mechanics. Like Arthur and Camelot, and like the game’s humbled heroes, Pendragon is a glorious ideal that — over time — is undone by its limitations. But like Arthur and Camelot it’s still truly inspiring, and its best playthroughs redeem it dozens of times over.

Pendragon wants to help you tell a story of the last days of King Arthur, and how much that idea appeals to you is exactly how much you’ll like it. Not every story works, but not every story has to.